Here’s what we didn’t do. We didn’t touch the Strength Knobs. In most cases, they aren’t the problem anyway. When a weapon is being used as intended, it should feel overpowered. So most imbalances come from using a weapon outside its role, in which case changing the strength knobs won’t fix anything, it will just make the weapon worse.

We also didn’t try to add a weaknesses. It often feels like the only option, but find something else! That sort of “a little hot, a little cold” design never ends. You’ll just chase your tail until you run out of time.

Your strategy should be to find where the element is being used outside of its designated role, and change the mechanics to constrain it better.

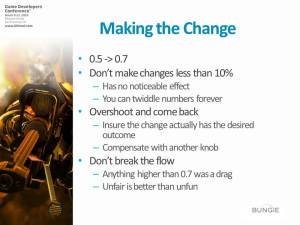

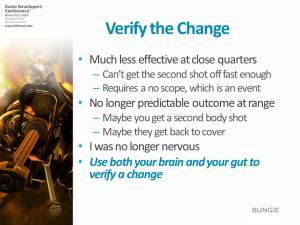

But if you can’t touch the Strength Knobs, you have to touch the Flow Knobs. (Remember, there isn’t anything else, because we removed all the extraneous mechanics!) The tricky part is to fine tune those Flow Knobs without losing the flow state you worked so hard to capture. Revisit them in light of what you now know about the game and don’t change them so far that you break flow.

Of the components of flow, cadence is the most flexible, so many problems can be fixed by adjusting cadence. Hopefully not so far that you lose the rhythm.

Most importantly, at this point you must not rely on your gut, it will steer you wrong! You need a very clear chain of cause and effect, so you can make as small a change as possible to fix the problem.

So what are the possible flow knobs we can tweak? What will achieve the balance objective with the least amount of ripple effect?

We could have changed the number of shots in a clip. That would have changed the cadence to cause the player to reload more often. But it would also have meant a sniper couldn’t kill two enemies without reloading unless he got a headshot. That would have ratcheted up the pressure quite a bit, and moved the Sniper Rifle out of the skill range of most players.

We could have increased the length of the reload. But dying because you can’t fire back is frustrating. To be honest, this change was a contender, but it felt too much like adding a weakness.

We could have changed the time to it took the Sniper Rifle to reach full zoom. We actually tried this as a solution (and found some bugs in the camera code, too!) But in the end, it encouraged players to fire without zooming, which broke the role worse than the original issue. In fact, it exasperated the problem of players using the Sniper Rifle at close range.

We also could have prevented the Sniper Rifle from doing headshots when unzoomed. Unfortunately, this removes a uniquely cool moment, which even average players can experience if they get lucky.

We could have changed the maximum total ammo. The problem is, this would have limited the overall effectiveness of the Sniper Rifle without changing the experience of any individual combat encounter. (For more on the perils of this technique, read Against Statistical Design.)

Finally, we could have changed the time between shots. We didn’t choose this option immediately; we tried, tested and reverted almost every value on this list. In the end, increasing the time between shots was the only one that fixed the balance problem with a minimum of side-effects.